He taught Bob Marley how to sing, refused to tour the world and turned down fame and fortune to live in a shack. Famously reclusive, he’s not an easy man to see live. This was a chance to redeem myself and experience a piece of reggae history.

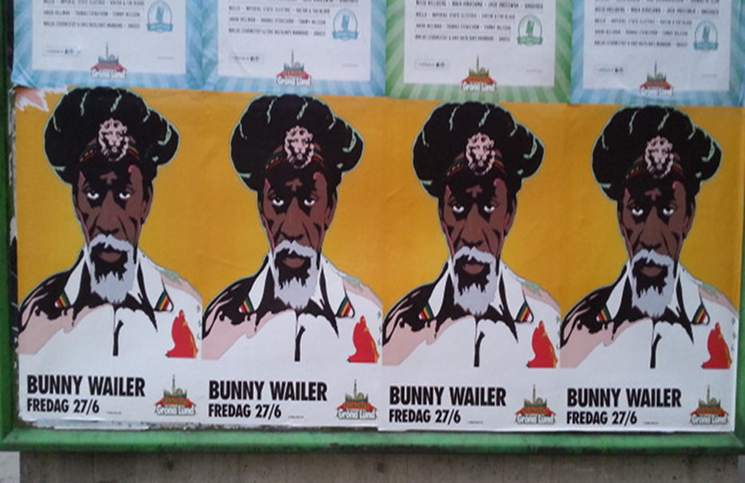

He came decked out in white, splashed with glitter and gold. A waistcoat striped in rasta colours covered his thin frame. His salt n’ pepper dreads were coiled into a crown. A lion medallion headband circled his forehead. He looked every part the high priest of reggae that he is.

Answering to either Neville Livingstone or Jah B, he is the last surviving member of The Wailers.

Answering to either Neville Livingstone or Jah B, he is the last surviving member of The Wailers.

Things weren’t always shiny. Bunny grew up with Marley in the ghettoes of Trenchtown (they’re stepbrothers). This was a world that smacked of poverty and violence. A place where they turned sardine cans, bamboo and discarded electrical wire into their first guitars.

It’s also the place where the trifecta of reggae – Peter Tosh, Marley and Wailer – formed their legendary band circa 1963.

“They created not just The Wailers but a new template for sound…The majority of them came from the same housing projects and were singing in large part to get out of them. Partly it’s this yearning, a brilliant hungriness, that you hear”. John Jeremiah Sullivan, GQ Magazine

Back up band Solomonic Reggaestra played two songs to the impatient crowd before the MAN himself turned up. His beard may be yellowish-white – and he doesn’t look like this any more – but the voice remains. Clear, a little husky and punctuated by spirited bellows every so often. I can’t get over his wiry, “stubborn old man” vibe that has seen him outlive the other reggae greats.

He became increasingly disillusioned just as The Wailers became an international success. Even though Bunny composed some of their most enduring songs – “One Love,” “Who Feels It Knows It,” and “Pass It On” – he was always overshadowed. Not for lack of creativity (he’s often called the best singer of the trio) but the way stardom was affecting him and his faith.

His arrest in 1967 for possession of marijuana though he wasn’t carrying any, added to the further fractures in the band (a popular misconception is that Jamaica’s some kind of pot heaven. It’s not. Public smoking lands you in jail). The trio split when Bunny no longer wanted to leave Jamaica to tour.

“When he ditched the Wailers he famously went and lived in a ramshackle cabin by the beach, surviving on fish from the sea and writing songs”. GQ Magazine

As Tosh and Marley gained international stardom, Wailer disappeared into the hills for 3 years and rumours of his ascetic Rastafarian life drifted out. No one thought he would sing again.

But he re-emerged in 1976, releasing Blackheart Man. Considered a masterpiece, it explores repatriation in “Dreamland” and incarceration in “Fighting Against Conviction” (written during the 14 months of prison).

The album’s cryptic lyrics cemented Wailer as a musical shaman and spiritual messenger. He lives up to that reputation by frequently appearing on stage in flowing robes, bedecked like some desert preacher of old. (He’s a high ranking member of the Nyahbinghi order in the Rasta movement)

If reggae is the Carribean version of soul, then he is the grandmaster of the genre. His songs are a blend of socio-political commentary and danceable melodies inflected in the heart of all good reggae.

“The reason the great Jamaican stuff deepens over time, over years, not with nostalgia but with meaning and nuance, is that it’s a spiritual music. That’s the anomaly underlying its power”. GQ Magazine

Bunny told the crowd “I can see the birds flying around. They’re enjoying themselves. They know what we are delivering. And they are saying to us – never stop. Breathe!”

His performance was bittersweet, punctuated with brief musings, regularly making references to Jah. He would single out individuals in the crowd, look them hard in the eye and sing, REALLY sing to them. At points, bliss would take over his face and he would dance the dance of the inspired. At 67, his moves were still solid.

His performance was bittersweet, punctuated with brief musings, regularly making references to Jah. He would single out individuals in the crowd, look them hard in the eye and sing, REALLY sing to them. At points, bliss would take over his face and he would dance the dance of the inspired. At 67, his moves were still solid.

My gripes about Swedish concert-goer’s lack of enthusiasm are well documented. Fortunately, a group of young rastafarians dressed in fatigues common to the religion, happily skanked down next to me, waving flags of Haile Selassie and Bunny.

Their energy was infectious and pretty soon a circle of ridiculously happy dancing humans formed as he sang on. The rastas cheered when Bunny nodded his head in acknowledgement.

Since Marley’s death, he’s continually honoured the memory of reggae’s greatest legend and tonight was no different. He ended the concert with his rendition of “No woman, no cry” and said “Reggae music is the greatest in the world”.