For nearly 30 years, Git Scheynius has been passionate about increasing female representation in the film industry and she knows what it takes to achieve this seemingly lofty goal.

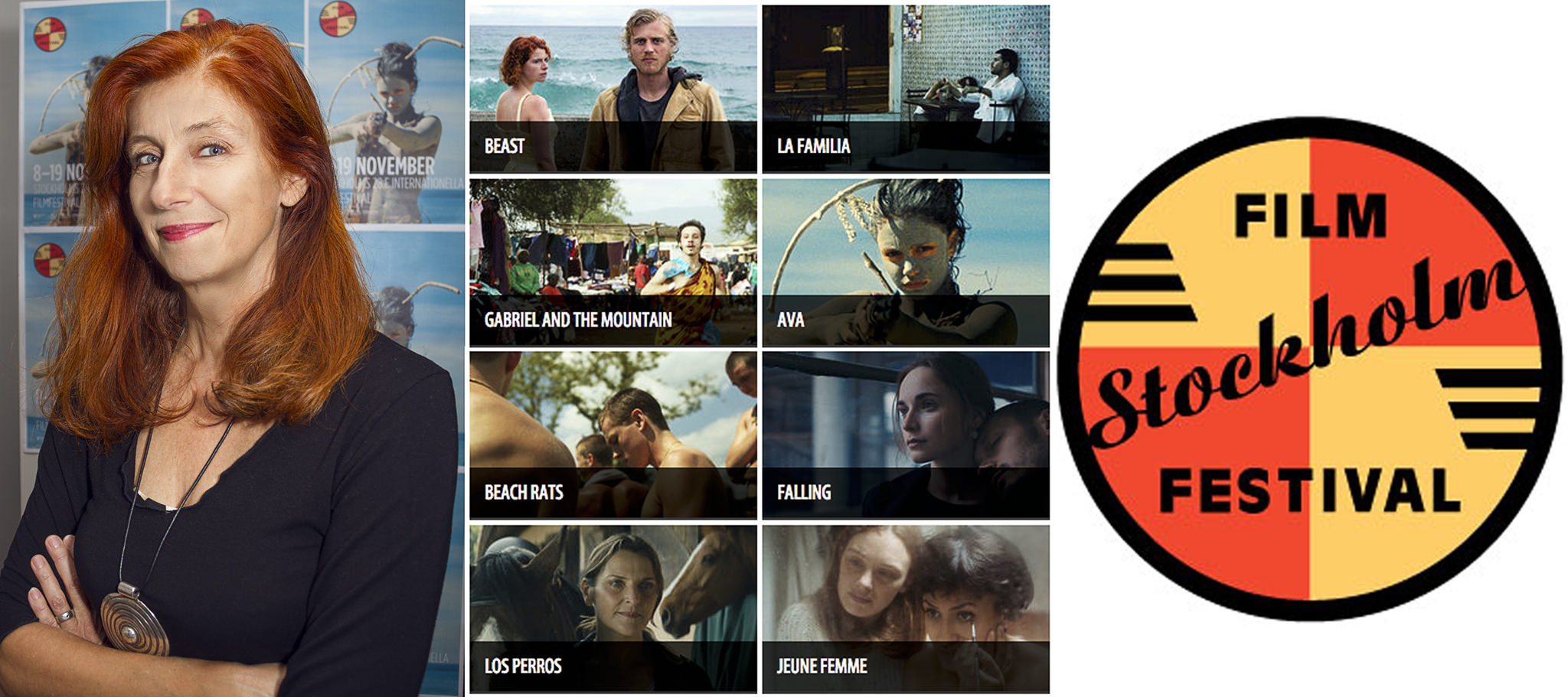

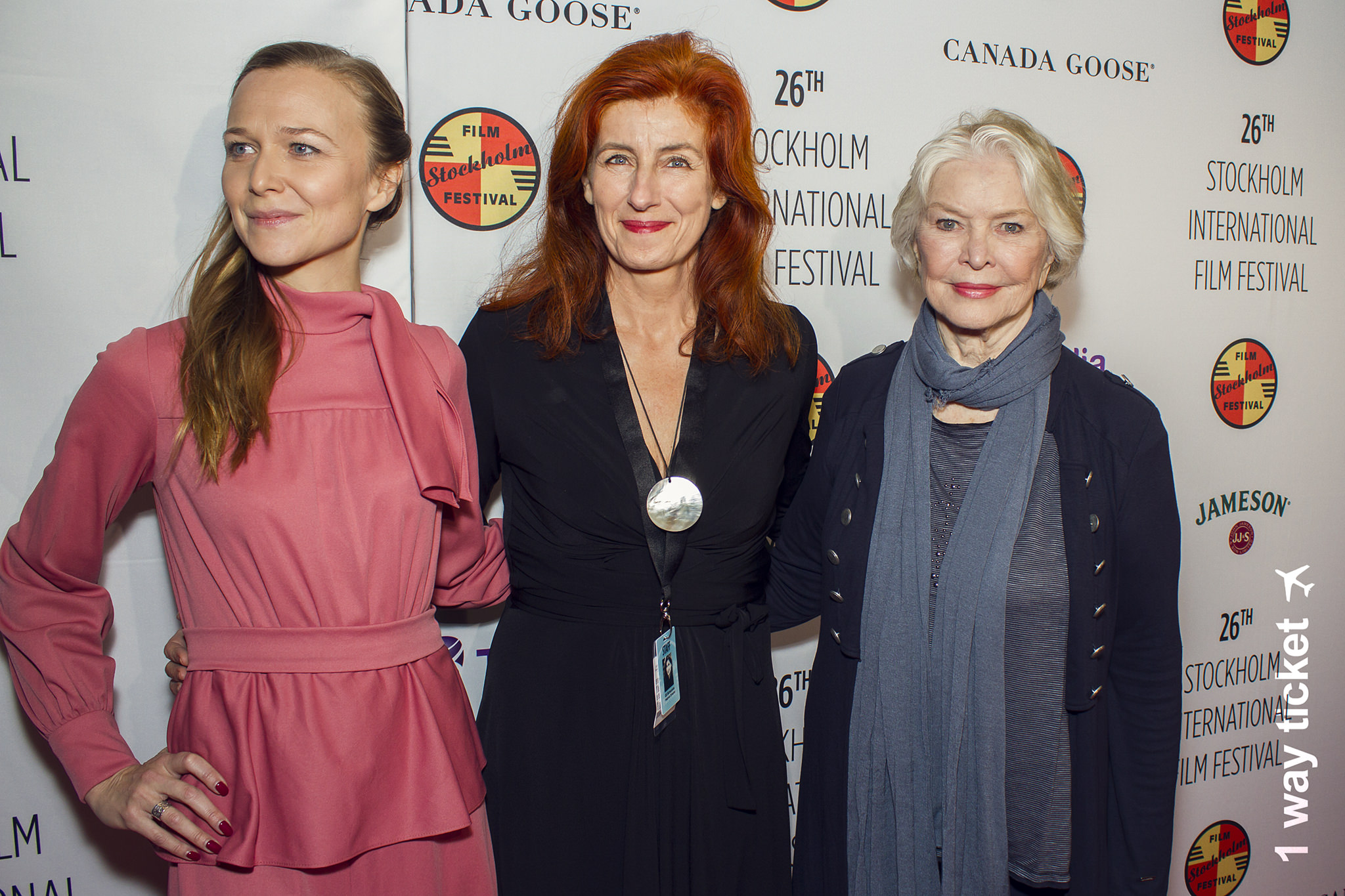

When it comes to gender equality in the movies, there’s a lot of talk about the wage gap between male and female actors, but there isn’t always enough attention paid to an equally, if not more, vexing set of problems: the dearth of female narrative perspectives, directors and producers compared to their male counterparts. Your Living City was privileged enough to sit down with Git Scheynius, the director of the Stockholm International Film Festival, and hear her thoughts on what the film industry needs to do to improve this situation. We’ve put together an excerpt of our inspiring conversation, and hopefully you find Git’s words as uplifting as we did!

Your Living City: In what ways does the Stockholm International Film Festival promote gender equality in the movies?

Git Scheynius: Well, when it comes to the way that we lift female directors, if you allow me to take the history of it, I was one of the founders of the Stockholm International Film Festival in 1990, so I’ve been working with this for almost thirty years. In the beginning I was young and it was very important for me that every female director knew that her film was picked or programmed because of quality and nothing else. I realized that the industry was so male-dominated and of course the first reflection I had on that is that I wanted to change that. But I was very reluctant to do any political changes, because all the directors I talked with said to me: don’t make a female section or anything, because all we wanted to do was a film and we can’t stand or humor more selections. In the beginning I thought this was something that history should change. Then I realized that if we wanted to see more female directors before I die, we had to do something. So ten years later, in the year 2000, we started to work on this in a stronger and more selected way. What we did, or what we prefer to do, is that we look at every female project that we see, and we see over 4,000 films every year to select 150. We work harder than the big festivals on that, because as you know ,Venice and Cannes film festivals consist of very few or no female directors in their competitions. So we work very closely with over 200 film companies and pick out the female-driven or directed films, and that’s also a [conscious] selection you could say. But it’s the same spotlight that men have had for a hundred years, as the film [industry] is over a hundred years old.

YLC: That’s really interesting and it seems you were also trying to get to the point that, OK, we’re not just trying to get women. It’s also about quality and that quality female films and female directors are out there, but they’re just not getting enough attention in a male-dominated industry. So how do you think the film industry at large, and obviously it’s in different forms in different countries, can be more supportive of female representation, and not just with actors, but also with producers and directors? What does the film industry need to do?

GS: A lot. You could say it’s like the society as a whole. You could say in short: follow the money and see whose pocket it’s in. Since we have a very male-oriented industry, those who decide whose film will have the biggest budget are men, and they are closer to their own stories. The important thing here is not maybe that the director is female or a woman. The most important thing is that we have stories about women, or women’s reflections on women’s society. So there have to be more female perspectives on the screen. At the Stockholm Film Festival as a whole, every year since we started for 27 years we have had 50-50 [men and women] in our audience and then you wonder why don’t we have more films with the female perspective?

We have a junior festival for children and we are creating films together with them. We also have a competition where children from all over the country can send in films, it’s called One Minute Films. It’s a short format, and the children are between six and nineteen, and every year it’s 50-50 boys and girls. There’s no difference. So if you look at that statistic, you can see that there are girls who like to create films, there are no differences when it comes to technique or a story to tell or the passion and ambition to make films. It’s totally equal. So the interesting part is what happens when you move it [filmmaking] to the industry? We work globally, we screen 150 films from 60 countries, and if you look at production worldwide, you see that about 10% of all films are made by women. That’s an enormous difference. When you look at literature, theater, and art, at least in Scandinavia, it’s completely equal in every case with the exception of film. Why? The answer is money and power. So it’s certainly a structural problem.

YLC: Would you say that’s because it’s traditionally been men who have had money and power, so they continue to financially support projects that appeal more to them as a group or that maybe perhaps more than other artistic industries, film is really driven a lot by money in a different way than, for example, the literary world?

GS: Film has two faces: the commercial and the artistic. Of course commercial films can be of high artistic quality. Of course. But you have to realize there are two different ways to do films. The commercial way brings in the money and the cultural [artistic] way is because you want to tell a story and then of course you have to finance it, but you have something in your heart that you want to get out. With the reservation that we don’t produce films and aren’t in the production industry, my view on this is that when it comes to [deciding] on a film, if you have a board of five men who decide which story to [take], of course it’s a safe play to take a story that you really believe that you know about. We did a very quick investigation just by taking the catalogue from last year’s festival, which consists of 200 films and looked at all the male projects—what are they about? We found out that 70% were about men and we did the same thing with female projects and discovered that about 60% were about females. What does this tell us? It tells us that the first film you do or the second or the third film you do, you create things that are very close to you, coming of age films or about the first love or a conflict you are involved in—it’s natural. So when it comes to decisions about whose film will be made, if you have a board and at least half of them are women, then you have another perspective. Another thing that I think is very strange, is that if you look at who consumes culture and film, there are more female consumers of culture and actually also film, not much, but about 60% are women. So they [men] should think more about who’s buying those tickets.

YLC: Right. And so few films, at least commercial films, have given really nuanced and insightful portrayals of women and their lives, and how complicated women’s lives are, and this can be frustrating for many female moviegoers. It can also be frustrating that the film industry seems more sympathetic to male characters who are imperfect or have fatal flaws, rather than female characters. What do you think about these portrayals of women that can so often be so one-dimensional?

GS: I’d like to take an example if you’ll allow me, because this is our campaign picture this year, so we can talk about this film because this is very typical. It’s a first-time film by Léa Mysius and it’s called Ava. She’s a woman of course and she’s done a coming of age story. It’s a girl and she’s thirteen years old and it’s such a great film and you also have the imperfect mother here. I love the character of the mother, because she’s good and bad as most people are, so it’s not one-dimensional. So this is a film that’s exactly what we’re looking for and what you get if you’re looking for a female director, this is a typical film. Léa Mysius is I think about 30 years old and often the first time is about growing up. It’s exactly the same when men do a film, but if you have like ninety percent [of films] about men growing up, how can you identify yourself with that? So this is important, to have the stories on the silver screen.

But it’s also important that women get more attention, because if you get a film prize, then it’s much easier for you to gain the money for the next production. We know that, so we want to support that. That’s the reason we have 50-50 in our competition and we work very hard on that because we always pick the films that have the highest quality. So to do that we work harder. And what you can see since we started this project in 2000, we don’t pick the winner of course, it’s an independent international jury, but what they have is half and half [male and female directors to choose from] – so what happened? Female directors won the prize [for best director] half of the time. So there is of course not any difference when it comes to quality – this is proof of it. And if…well, I don’t know if you’ve read about Venice and Cannes, but it’s quite irritating because, for example, Venice says in an interview with Hollywood that it’s not in our hands to lift female directors if there aren’t enough female projects going on out there. So what they do is point at the production companies instead. But our [approach] here is that we think it’s our responsibility to lift up female directors. It’s very important that female directors get prizes, because when you get prizes you get interviews and you get more press and publicity and then you have the possibility to gain the money for your next production.

YLC: These are excellent points, and really underscore the importance of being committed to making conscious structural changes in the various branches of the film industry. There’s also another issue we’d like to touch on with you. When talking about gender and men and women and the movies, we’re also expanding our understanding of gender and focusing more on the experiences of queer, trans and non-binary actors, directors and filmmakers. Do you feel like they are playing a bigger role at the festival than ever before?

GS: Yes in fact they are. We have always been interested in queer projects, and that’s always been a big theme at the festival, and over the last three or four years the quality of these projects has risen a lot and I think that’s because we have a more open society now. So producers and film companies are more eager to support [queer] projects. This support leads to better quality and visibility for queer films, and this year we have seven really good [queer] films and I’m really happy about that.

YLC: That’s great to hear. Well we’d like to thank you so much for taking time from your busy schedule to talk to us! We look forward to catching some of the movies and sharing them with our readers.

GS: Yes—thank you!

The 28th annual Stockholm International Film Festival runs from November 8-19 and Your Living City will keep you updated with all the latest info. Make sure to check out the films as well as a Face2Face event, where you can come in contact with directors and producers and hear their words of wisdom. For more information about the festival program, visit the SIFF website at http://www.stockholmfilmfestival.se/en